One thing I think should be pointed out—and which I haven’t come across in the legacy news—is the profitability of the oil that Canada will be putting into the new pipelines that Canada has built. Take a look at the following graph from Statistica that shows the relative price of producing a barrel of oil in 2015:

As you can see above, Canada produces the third most expensive oil in the world—$41 US in 2015. In contrast, Saudi Arabian oil cost only $10 a barrel. What this means is that the ‘break even’ price of Canadian oil is 4 times that of Saudi oil.

This isn’t the result of lazy workers, the perfidious Liberals, or, environmentalists getting in the way of hard-working oil executives. It’s simply a fact that it takes a lot of engineering and energy to get the oil out of the soil it’s been soaking in for millions of years. Moreover, the tar sand mines are a long distance from ice-free shipping. In contrast, all Arabia has to do is pump its oil out of the ground, put it through a short pipeline, and, load it on ships. It’s simply a question of the laws of thermodynamics and geography, and no amount of engineering or capitalist ingenuity can change that.

Next, here’s a chart from MacroTrends.net that tracks world crude oil prices by year.

As you can see, the price of oil on the world market is extremely volatile and periodically dips below the Canadian cost of production. Those are the ‘busts’ in the Albertan economy that is referenced in the meme I posted in the previous article (ie: “Please God give me one more oil boom and I promise I won’t piss it away”).

The issue this raises for me is that if the world really does want to prevent a climate change catastrophe, it will need to start using less and less oil. And if the world starts to cut back, this means that the price of oil will decline fairly quickly as producers compete with each other for a slice of a declining market. And if that happens, oil from the tar sands is going to become too expensive to sell on the market—meaning that there won’t be money left to pay off the Trans Mountain pipeline or clean up all the orphan oil wells and other infrastructure.

Is this a realistic concern?

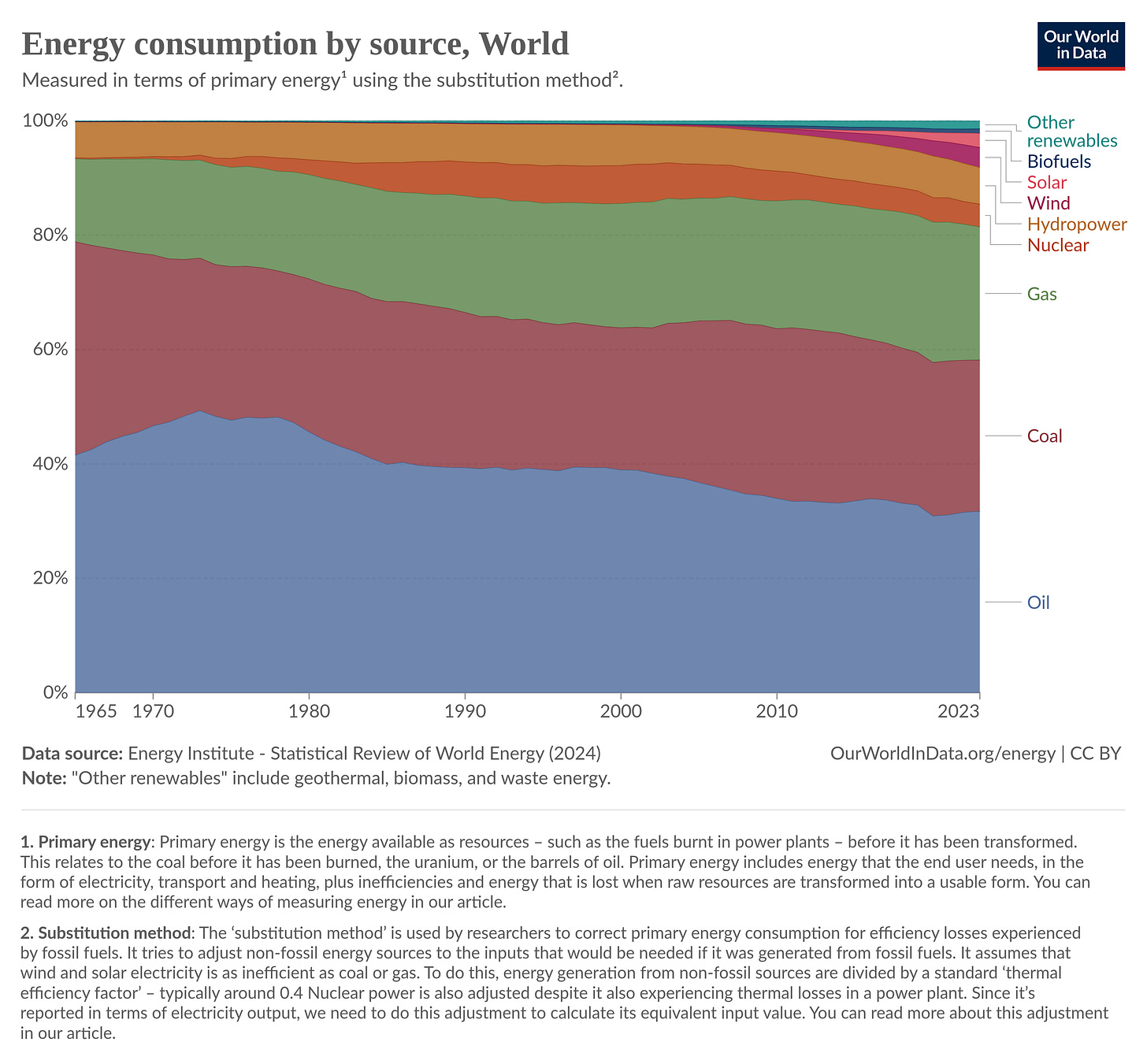

At first I just assumed it was, because I was thinking about the rapid introduction of electrification through renewable sources like solar and wind. This means that the relative percentage of energy that comes from oil is declining fairly significantly.

As you can see, oil peaked as a percentage of world energy needs in around 1975. The problem is, however, that this only shows a reduction in oil use if we assume that the total use of energy stays the same from year to year. If total demand increases fast enough, however, the total amount of oil used can keep going up even if it’s share of the total keeps declining.

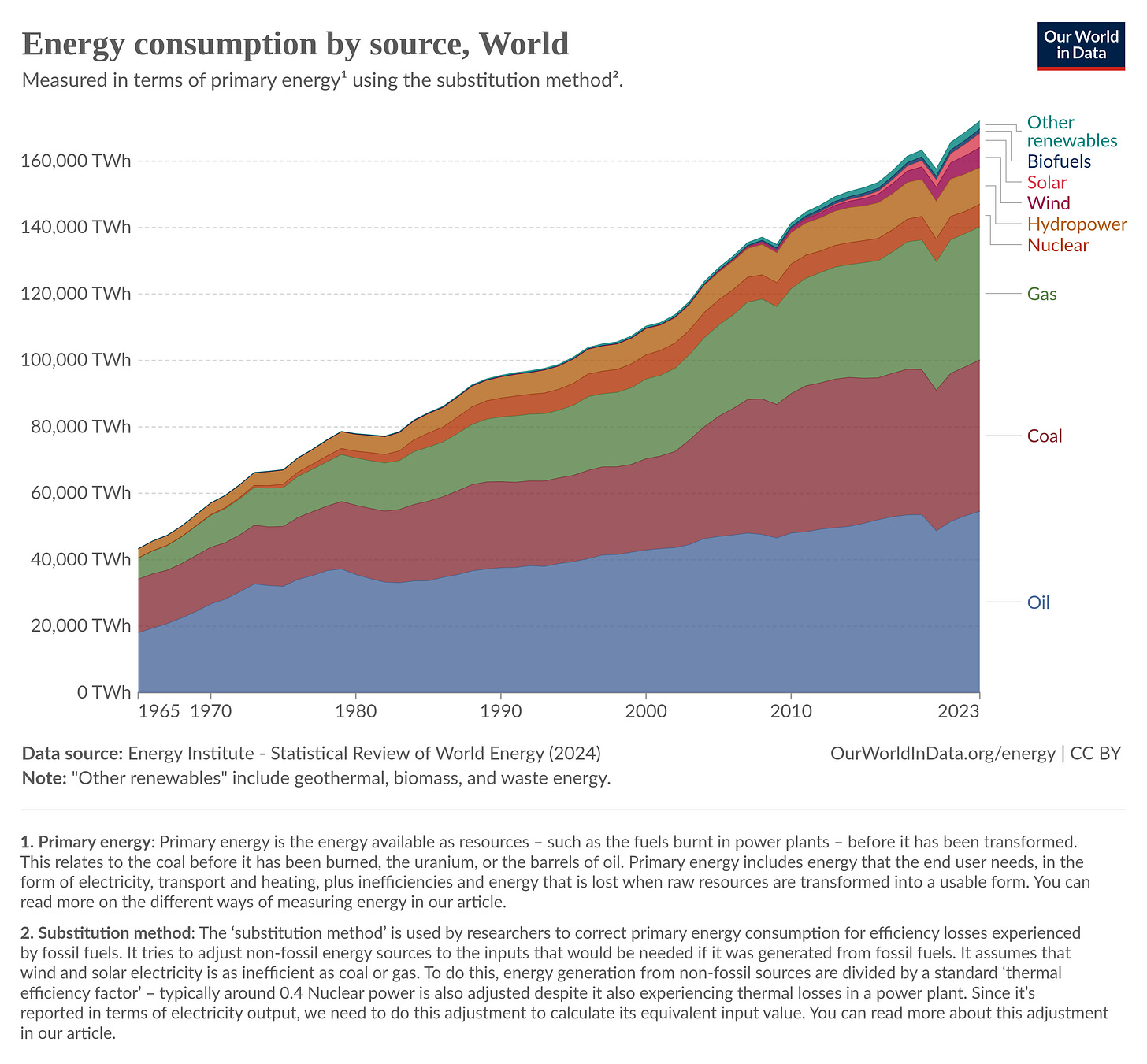

As you can see from the above graph, the amount of oil used by the world has gone up by about 50% from the late 1970s, even though oil’s percentage of the energy mix seems to have declined by about 25%.

This paradoxical situation explains how it is that we can have environmentalists arguing that oil is a bad long-term bet for Canada, and, oil executives saying that it’s a slam dunk. I suspect the difference comes down to two things:

how concerned you are about the Climate Emergency

how much you care about the long-term economic prospects of your country as opposed to short-term profits for your company

If someone (like me) feels that the Climate Emergency is an existential threat to human civilization, you are going to want us to get off fossil fuels ASAP. In this scenario, we need to assume that we are going to get off oil and onto sustainables very soon. And once we hit the point where oil is not only declining as a percentage of the energy mix—but also in absolute terms too—there is going to be a scramble by oil producers to sell as much of their oil as possible before the demand dries up and they are left with stranded assets.

In that scenario, it won’t take long for oil to drop below $41/barrel. At that point Saudi Arabi will still be making $30/barrel in profit—but the tar sands will go bankrupt. That means that there won’t be any money for the costs accrued to the nation by the oil industry such as the cost of cleaning-up abandoned oil infrastructure. (I discussed those in a previous article.) It also means that all the money the country has invested in pipelines and the carbon-capture ‘fairy tale’ will have been thrown away.

At the same time, the people who built their careers around the oil industry will find themselves out of work. And the province of Alberta will find itself stuck in a situation where its economy is collapsing with no obvious alternative to fall-back on. Moreover, when this happens large swathes of the Albertan electorate will have been trained to believe that it was all the fault of Ottawa and/or environmentalists and had nothing to do with their own personal decisions—which will create another yet another stupid constitutional crisis for the nation. Revenue will fall while the cost of governing will be going up dramatically due to mass unemployment. This will not be a pleasant time.

My suspicion is that the people running both the oil companies and the governing class in Alberta would mostly dismiss the above scenario as being the ravings of an environmentalist alarmist. But I can’t help but think their willingness to play chicken with climate change is only supported by motivated reasoning. IMHO people who’s money and power is totally dependent on oil are shoving their fingers in their ears and humming loudly whenever someone like me warns them about the future.

There’s another issue I want to raise that I think might be useful to consider.

Here’s an excerpt from a recent report by the Bank of Canada

Productivity is a way to inoculate the economy against inflation. An economy with low productivity can grow only so quickly before inflation sets in. But an economy with strong productivity can have faster growth, more jobs and higher wages with less risk of inflation. That’s why I want to talk about Canada’s long-standing, poor record on productivity and show you just how big the problem is. You’ve seen those signs that say, “In emergency, break glass.” Well, it’s time to break the glass.

(Carolyn Rogers, Time to break the glass: Fixing Canada’s productivity problem, March 26, 2024)

So productivity is important. But what is it? It isn’t about how hard each individual employee works, but rather how well trained they are and what sort of tools they use to do their jobs. For example, if you are writing computer code you are going to want to have the best coders you can working on your project. Similarly, if you are cleaning snow off a sidewalk, you get a lot more productivity if your employee uses a snowblower than if they just have a shovel.

The quality of the tools that we provide to our workers is called Capital Intensity and the skills workers bring to the job is called Labour Composition. There’s a third measurement that’s a little harder to understand called Multifactor Productivity. Rogers defines it as

measures how efficiently capital and labour are being used. This can refer to intangibles such as how much competition a company faces, economies of scale, management practices and many others. It can also refer to how well companies are taking advantage of technologies such as machine learning and generative artificial intelligence.

(According to the Wikipedia “Multifactor Productivity” is the same thing as “Total Factor Productivity”—which comes up later on. I keep the original language in quotes, though, so try not to be confused by my switching between the terms. There’s value in an outsider’s view of professional expertise—but also pitfalls to consider too. As always, everything I write is provisional and I welcome corrections based on expertise and experience.)

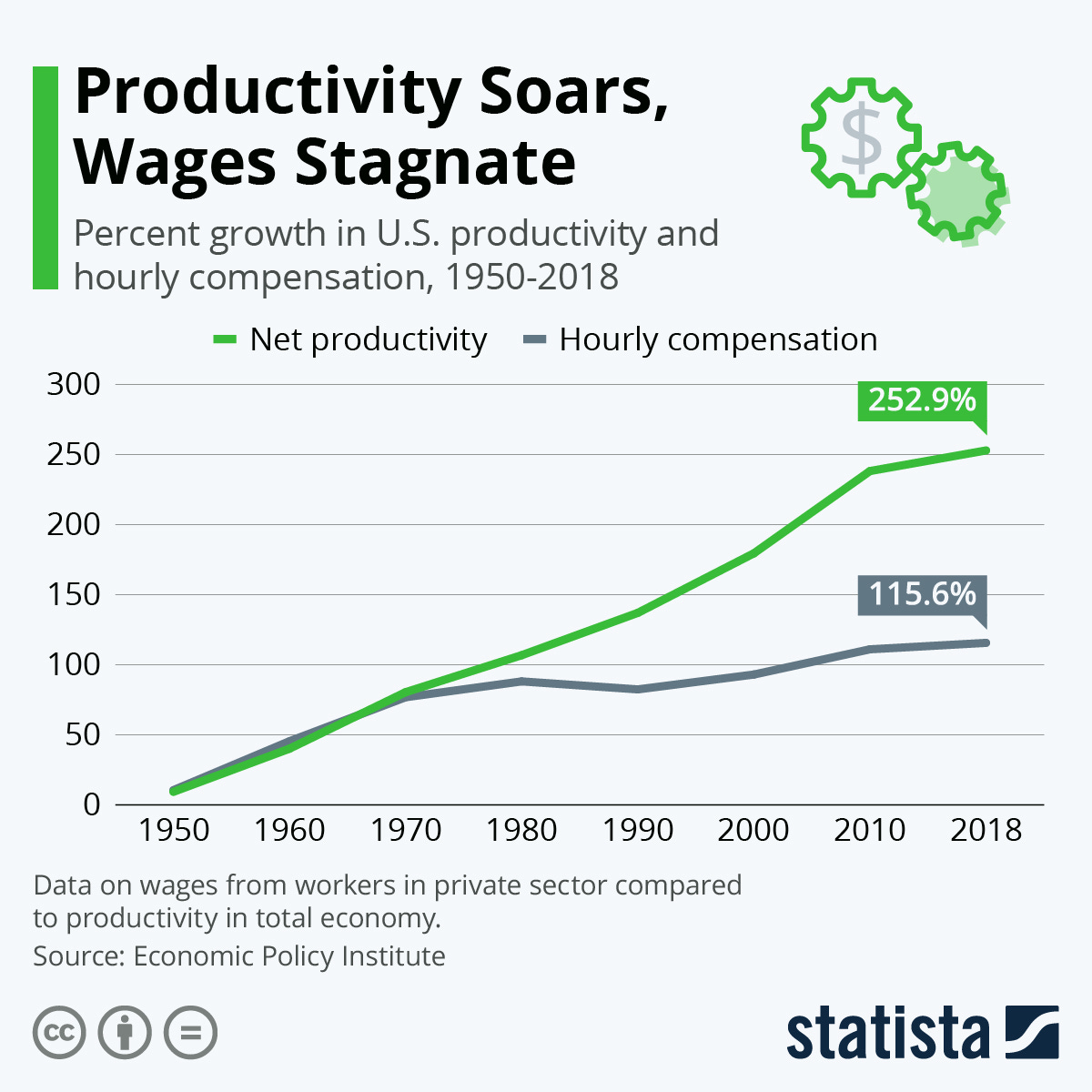

As I understand it—and I’m no expert—orthodox economics links productivity to increased wages. This is because—at least theoretically—increases in productivity mean that a company not only has more money to give owners, but also to give raises to workers.

Unfortunately, for one reason or another, in the late 1970s increased productivity ceased resulting in higher wages for workers even in places that had greater productivity than Canada—like the USA.

What this tells me is that while it is common knowledge among economists that productivity is necessary for wage gains—the experience of Americans would suggest that it isn’t sufficient. There needs to be some mechanism in place that forces businesses to hold back some of the profit they want to give to the ownership class and give it to the workers. Just off the top of my head, I’d suspect that the decline in the power of unions might have a lot to do with the above graph.

Why am I going on about productivity in an article that purports to show the background issues involved in Canada and the oil industry? It’s because I came across a paper by two McMaster University economists who are argue that Canada’s crummy productivity stats are the result of our reliance on the oil industry: Canadian productivity growth: Stuck in the oil sands by Oliver Loertscher and Pau S. Pujolas.

Their argument—in a nutshell as understood by a non-economist—is that the oil sector in Canada is so large compared to the others (service, agriculture, and, manufacturing) that it has an outsized effect on the ‘Total Factor Productivity’. I looked on line to try to find an easy-to-understand definition of this term, and the best simplification that I could find was this:

The total factor productivity (TFP) is a number that showcases the productivity of a business by determining how much it produces versus what it needs to spend to achieve that result. In simpler terms, it is calculated by dividing your total production (output) by average costs (inputs).

Loertscher and Pujolas go to the trouble of separating out the TFP in the Canadian economy according to different sectors over the last few years and get an interesting result.

In essence, the lack of TFP growth is entirely accounted for by excluding the Oil sector from the Canadian national accounts and recalculating TFP accordingly (we refer to this measure as “Net-of-Oil TFP”). From 2001 to 2018, Canada’s TFP grows at 0.06 per cent per year. By contrast, Canada’s Net-of-Oil TFP grows at 0.60 per cent per year, a similar rate to that of the United States (0.47 per cent if oil is included, 0.49 per cent if oil is excluded).3 It is important to note that TFP does not account for the positive effects of rising oil prices.

As you can see, every other sector of the Canadian economy has increasing productivity numbers but oil production is drawing the average down. This dramatically lower productivity seems to be explained by this graph I found in Wikipedia and which was created by a geologist and engineer is supposed to be based on info from OPEC data:

Notice how as the relative percentage of conventional versus tar sands oil declines, so too the Total Factor Productivity declines in the Canadian oil sector—which drags down the average TFP for the entire economy. The problem is that baking oil out of dirt in a giant open-pit mine is just inherently less efficient than pumping it out of the ground. And the higher the percentage of oil that Canada produces this way, the lower the productivity in the oil sector.

Loertscher and Pujolas merely point out the way productivity numbers are squewed by the tar sands without stating a case one way or the other about whether this is a good thing.

While we believe that our result sheds light on the underlying cause of differential evolution of productivity between the two countries, it should be used with caution: we find that the oil sector can explain, in an accounting sense, the lack of Canadian TFP growth. Our findings do not, however, make a judgement on the desirability of this result, nor getinto the debate surrounding an industry that confronts a host of challenges, such as carbon emissions.

Namely, it is perfectly plausible that the Canadian economy is responding optimally by exploiting a resource when its value is very high. Whether this represents the best course of action is a question that requires further exploration. Consequently, we defer the answer to this crucial issue to future research.

At this point, the obvious question is whether or not this dramatic lowering of productivity in one key sector of the Canadian economy merely just squews skews the numbers with no effect on any of the other sectors—or operates like an anchor hanging around the neck of everyone else. I’ll talk about that in my next article on this subject.

Is squews Canadian for skews?

Otherwise, fascinating series. I've often said that Peak Oil doesn't mean that all the oil is gone, just the half that was easiest (cheapest) to extract.