An Interview With Marian Thorpe: Part One

The author in conversation with Bill Hulet about her latest in the "Empire's Legacy" series.

I recently had the opportunity to have a conversation with Marian Thorpe, inspired by a read of her latest book in the “Empire Legacy” series: Empress and Soldier. The book is based on an approximation of the Roman Empire, but is seen from the viewpoint of two people who are given an exceptional vantagepoint for the time. This allows Thorpe to open a window on a society very different—and yet, very similar—to our own.

The novel is split between two characters, Eudekia and Druisius. The former is the daughter to an advisor of the Emperor and who is also the Patron of latter’s family. Through a series of chance meetings and improbable steps, she ends up marrying the heir to the throne. He succeeds his father, but dies in battle shortly thereafter. This leaves Eudekia Empress of Casil—in effect as well as in title. (‘Casil’ is Thorpe’s sort of, but not quite, stand-in for Rome).

Druisius follows a very different trajectory as he leaves his merchant father at a young age, joins the imperial army, becomes a spy for the military, and eventually joins the Palace Guards—and becomes a spy for them, and eventually ends up working directly for the Empress Eudekia.

This is a stand-alone novel in the series—which now has seven installments. If you are interested in this genre, I’d recommend the book. (I’ve started the first novel in the series, Empire’s Daughter, because I’m intrigued by the premise.)

What follows isn’t primarily a conversation about the book, per ce, but rather more of a discussion of issues raised by it. They cover writing-in-general, historical fiction in particular, and, the nature of human consciousness.

I was really impressed by Ms. Thorpe. She’s sharp as a tack, and seems to have a broad-ranging interest in the outer limits of what it means to be a human being—without losing touch with the day-to-day practical realities of life. I’d consider her one of those people that makes Guelph such an interesting place to live.

I did some research and found that report I mentioned in our conversation. It was published in 2018 by the Samara Centre for Democracy and titled Beyond the Barbeque: Reimagining Constituency Work for Local Democratic Engagement. It is part of a long-term, multi-year study that interviewed MPs who had left Parliament—either by retirement or by losing an election—and asked them a broad range of questions about their work. This particular report focused on the nature of their constituency work. That’s the sort of thing that I called ‘retail politics’ and what seemed to me to be similar to the ancient Roman ‘patronage’ system Thorpe describes in her novel.

The key issue that the report identified was how individual MPs have found themselves dealing less and less with actual legislation in Ottawa and instead find their days filled-up attending special events in their constituency (for example, the ‘barbeques’ in the title) and helping constituents like me cut through red tape.

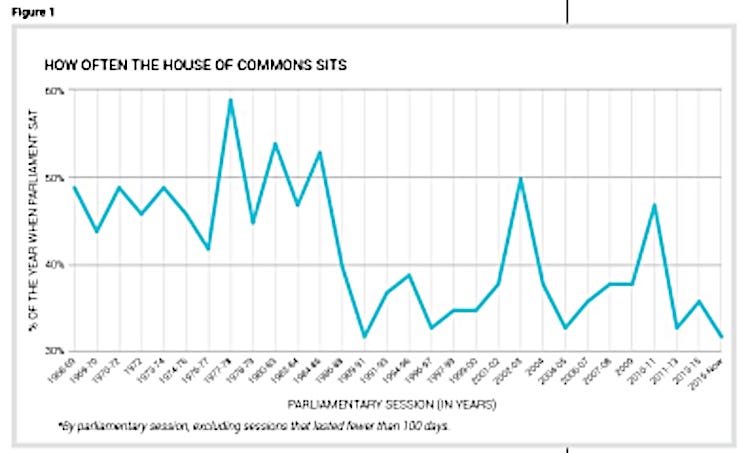

One of the ways the report shows how the MP’s job has changed was simply by pointing out the amount of time that Parliament spends in session. I was surprised to find out that this has dramatically declined over the period from 1968 to 2018, as the chart below shows. (I apologize for the quality of the graphic. I couldn’t find the actual study on the Samara website and was forced to locate somewhere else—and that site didn’t allow me to easily pull graphics from it. As a result, all I could do was get a screenshot from a small window—hence the low resolution.)

The big dip in the middle of the chart occurred between 1986 and 1988, which was when the Conservatives were in power under Brian Mulroney. But things never got back to the same levels as the 1960s when Chretien, Harper, and, now Trudeau were in power. This is obviously a tendency that transcends party affiliation. (I haven’t tried to look at recent years—the pandemic emergency measures would invalidate any of those numbers.)

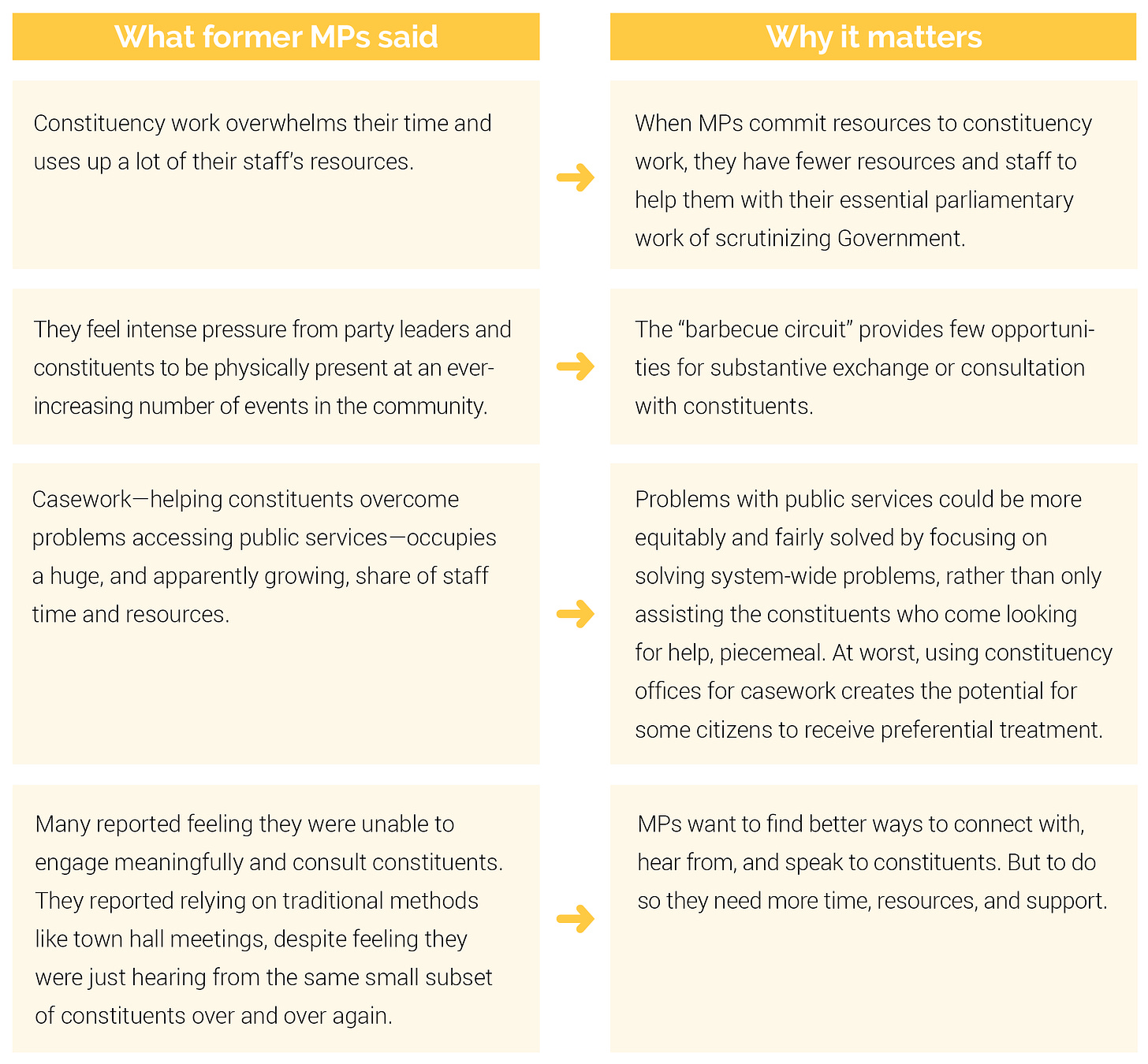

For MPs, however, this decline in participation in the development of legislation has been replaced with an never-ending stream of election glad-handing and becoming an ‘ombudsman’ who helps local citizens get through a bureaucracy that often seems to be designed to stymie the people it is supposed to be serving. The key findings of the study are as follows:

I’d like to draw readers attention to two particular statements in the above document. The surveyed MPs complained that:

The “barbecue circuit” provides few opportunities for substantive exchange or consultation with constituents.

and

Problems with public services could be more equitably and fairly solved by focusing on solving system-wide problems, rather than only assisting the constituents who come looking for help, piecemeal.

Think about the three data points I’ve mentioned above:

Parliament meets significantly less frequently than it did 50 years ago

MPs are forced by their parties to spend less time on legislation and engaging with their constituents on a deep and personal level, and more on empty ‘glad-handing’ at facile public events

The public increasingly sees them as informal ‘social workers’ who’s real job is making an increasingly opaque and dysfunctional civil service work for those individuals who have the ability to access their office

Does this seem to you as a democracy that is robustly serving the public? Or as an increasingly top-down system that is failing to adapt to present-day problems? I was intrigued to see Thorpe’s description of the Castil/Roman patronage system in action—especially with regard to navigating the bureaucracy. (The more things change, the more they stay the same.)

There’s an adage to the effect that ‘those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it’ and another that says ‘history does not repeat itself, but it rhymes’. These are both saying that one way of understanding the present is to take a good look at the past. I generally support this position—with one strong caveat. We have to get the history right.

The academic study of history is a strange beast. It purports to be about the past, and presumably the past doesn’t change. And yet, as historians gain more information, they are constantly revising what they say about it. To a large extent this is a product of the fact that what we think about ourselves is often deeply influenced by what we say about our ancestors. And what we say about them often comes about as a result of the politics of today.

If some readers wonder what I’m referring to, consider how much the historical school called the “Lost Cause” has influenced American politics from the end of the Civil War up until today.

Yup, all that fuss down South about things like confederate memorials and so-called “Critical Race Theory” is the result of a historical movement designed to control the historical narrative about the Civil War.

This isn’t just an American thing. Stephen Harper was very interested in the stories that Canadians tell each other about our history, which is why his government made a big fuss about the two-hundredth anniversary of the War of 1812.

“The War of 1812 was a seminal event in the making of our great country. On the occasion of its 200th anniversary, I invite all Canadians to share in our history and commemorate our proud and brave ancestors who fought and won against enormous odds. As we near our country’s 150th anniversary in 2017, Canadians have an opportunity to pay tribute to our founders, defining moments, and heroes who fought for Canada.”

Stephen Harper as quoted by Matthew Barlow in Re-manufacturing 1812: Stephen Harper's glorious vision of Canada's past

In addition, the Harper Conservatives also spent about $5 million changing the dress uniforms of the Canadian Armed Forces to reflect the ‘glory days’ of WW II. The idea seems to have been to encourage pride in Canadian history when everyone pulled together to defeat the Yankee hordes or later when we joined a great international effort to destroy the Fascist menace. And the hope was this would push back against divisive political movements like Quebec Nationalism and the First Nation’s battle to create a place for themselves in settler society.

This doesn’t mean that I have a criticism of Thorpe’s work—far from it. She is very upfront that the world she is describing isn’t ancient Rome. It’s a series of fantasy novels that deal with an imagined world that is loosely based on Roman history. That’s why I was so happy to see things like a vision of how the patronage system may have worked, plus a comment in our conversation that this isn’t historically accurate because she is anachronistically projecting a system from the Republic onto the later Empire. This is fantasy not history—but it’s written by someone who has done the research and seems to know enough to be able to tell the difference between the two.

I think this is enough for one week. I’ll have more from Marian Thorpe in my next post.