An Interview With Marian Thorpe: Part Two

If readers are wondering what in the world we are talking about, Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind is based on two different phenomenon that are studied by psychologists. The first is the fact that human consciousness can manifest various phenomenon where it appears that more than one ‘being’ inhabits the human body. There are a lot of phenomenon that come under this heading—visions, voices, dissociative disorder, etc. Some are often considered symptoms of some sort of illness, but I’d argue that they are also simply part of one’s everyday life.

Let me illustrate with a couple examples that have happened to me.

I’ve practiced martial arts for something like 40 years. At one time, part of that training involved doing a sort of pseudo-sparring called ‘push hands’. This was a system that was supposed to teach us to remain ‘rooted’ in a stance while in contact with another person. We were both trying to attack each other while defending ourselves. The goal was to be able unbalance the other person and knock them over—while keeping the other person from doing it to you. (This is a big part of what separates martial arts taijiquan from the more commonly-known exercise taijiquan.)

One day I was demonstrating this training system with another person to a visitor to our school and something ‘clicked’ in me. Suddenly I’d grabbed onto my partner, did a back roll pulling him over me and down onto the floor, whereupon I ended-up on top—trapping him.

This was a totally unplanned, spontaneous move that I wouldn’t have been able to do on command if my life depended on it. I suppose I could call it an example of dissociation—but it was hardly a ‘disorder’. In fact, it’s the sort of thing that martial arts are supposed to foster in the individual. In Chinese, it is called “Wuxin” and in Japanese it is called “Mushin”. Usually this is translated as no mind awareness.

This isn’t something that only happens in martial arts schools and Daoist temples, however. When I proposed to my wife—for example—I just did it without any pre-thought or preparation. It just happened. In Daoist philosophy there is the idea that ‘being comes from nothing’, or, that a lot of life consists of stuff just popping into existence. This isn’t considered some sort of weird anomaly, but rather a common part of everyday life.

If this seems outlandish, consider the following. When you have an everyday conversation do you choose what you say to the other person? We often admonish our children to ‘think before you talk’—but how often is it practical to do such a thing? And even in those rare instances where people can ‘think before they talk’, what is the process going on in your mind when you do that? Isn’t it a case that a little voice in your head just rattles off some ideas and then another part of you then rattles off commentary about those words to help you evaluate them? Where did those other words come from?

Beyond this sort of introspective analysis that comes from contemplation, there’s also experimental evidence that supports the idea that what we call ‘unitary consciousness’ might actually be an overlay that covers up more than one thing we call ‘me’.

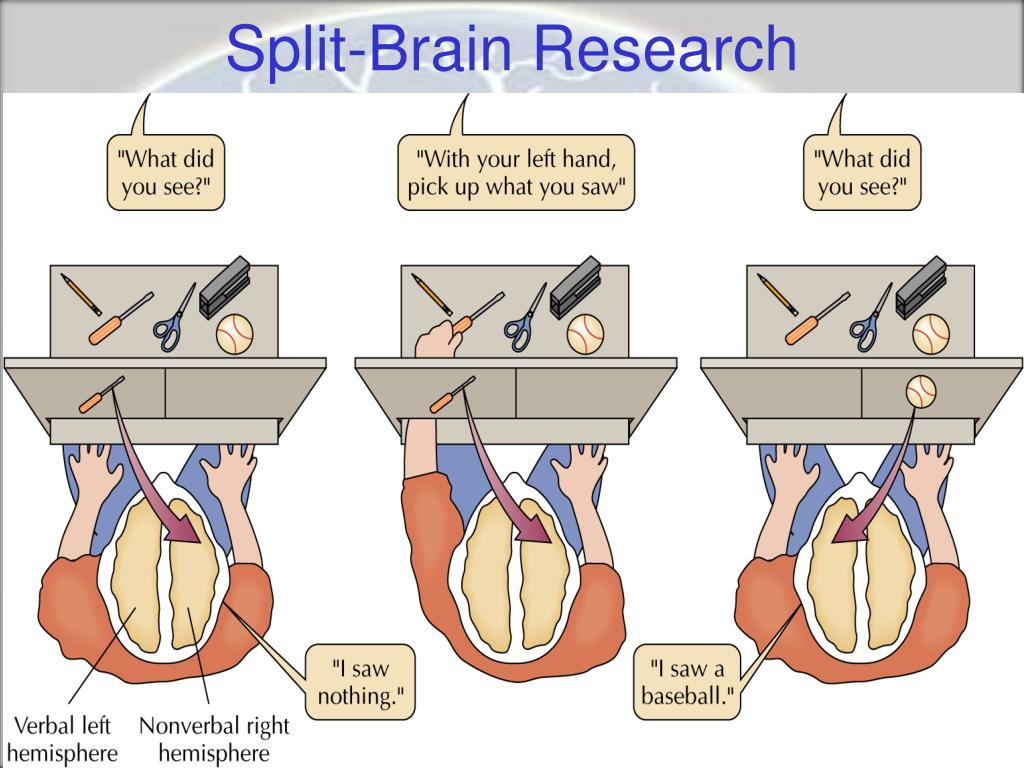

Consider the case of the split brain experiments. They came about because at a specific period in time a surgical procedure was used to help patients with an extremely debilitating type of epilepsy that worked by severing the connection between the left and right parts of their brains. In most cases this caused no discernible problems, but psychologists found subtle—but very interesting—changes in the way people interacted with the world. One of them is illustrated below.

The key points that readers have to understand about the above diagram in order to understand it are:

The left and right eyes can only see what is right in front of them. (In the real experiment a wall extended from the screen in front of the subject to their nose—this cut off the ability of each eye to see what was in front of the other.) So only the left eye can see the screwdriver on the first two figures, whereas only the right eye can see the baseball on the last one.

The brain of the subject has been surgically separated into left and right sides, and the subject’s ability to speak is naturally limited to the left hemisphere of the brain. (The human brain is somewhat asymmetrical, with parts of each side usually specializing on some particular functions and not others.)

The eyes of human beings are cross-connected to the brain—the left eye connects to the right hemisphere and the right one connects to the left half of the brain.

The interesting result of the experiment is the way the eyes, voice, and, hands interact. When the picture is presented to the eye that is connected to the verbal side of the brain, the subject can verbally tell psychologist “I saw a baseball”. But when it is presented to the eye of the person that is disconnected from the verbal side of the brain the subject says “I saw nothing”. But this isn’t entirely true, because the non-verbal part of the brain that controls the subject’s hands knows that he saw a picture of a screwdriver—which means he will reach under the screen and grab it instead of something else, like the scissors, stapler, or, pencil.

What this and other similar experiments seem to indicate is that these people have something like two different ‘selves’ in their body—beings that have been created by cutting their brains in half. The existence of this ‘second self’ is the ‘bi-cameral mind’ Jaynes suggests may have manifested itself as the Gods and spirits that dominated the lives of ancient peoples.

Jaynes built upon this modern evidence and suggested that when we read old religious and historical texts we can find suggestions that people literally heard and saw ‘Gods’ that spoke to them and gave them practical commands that they used to rule both their individual lives and the communities they inhabited. For example, he quotes the following examples that comes from the testimony from Conquistadors from a modern European civilization when who came into contact with two Meso-American stone and bronze-age civilizations that Jaynes believes were still using bi-cameral consciousness.

…Further direct evidence comes from America. The conquered Aztecs told the Spanish invaders how their history began when a statue from a ruined temple belonging to a previous culture spoke to their leaders. It commanded them to cross the lake from where they were, and to carry its statue with them wherever they went, directing them hither and thither, even as the unembodied bicameral voices led Moses zigzagging across the Sinai desert.⁴⁴

And finally the remarkable evidence from Peru. All the first reports of the con- quest of Peru by the Inquisition-taught Spaniards are consistent in regarding the Inca kingdom as one commanded by the Devil. Their evidence was that the Devil himself actually spoke to the Incas out of the mouths of their statues. To these coarse dogmatized Christians, coming from one of the most ignorant counties of Spain, this caused little astonishment. The very first report back to Europe said, “in the temple [of Pachacamac] was a Devil who used to speak to the Indians in a very dark room which was as dirty as he himself.”⁴⁵ And a later account reported that

“. . . it was a thing very common and approved at the Indies, that the Devill spake and answered in these false sanctuaries . . . It was commonly in the night they entered backward to their idoll and so went bending their bodies and head, after an uglie manner, and so they consulted with him. The answer he made, was commonly like unto a fearefull hissing, or to a gnashing which did terrifie them; and all that he did advertise or command them, was but the way to their perdition and ruine.” (Jaynes, p-196)

What would it be to live in a society where people go into a temple so they can literally talk to an idol and act on its direct orders? We still have people in our society who say that ‘God told him to do such-and-such’—as Thorpe points out—but it’s deucedly-hard to parse-out whether they mean it literally, in a metaphorical sense, if they lack the ability to differentiate between the two, or, they are just flat-out lying in order to bamboozle the rubes. (I suspect that all of these exist in any given community of believers—and even often within the same person.)

The writer of historical fiction is faced with the problem of trying to answer the question of ‘how similar should the consciousness of the characters I’m creating be to the modern reader?’ That requires the development of a theory of historical psychology. The problem is compounded by the fact that every time an author decides to incorporate a significant difference between modern and historical experience and sensibilities, she runs the risk of alienating her readers—.

This needn’t be as dramatic as having characters interacting with Odin or the Flayed God. Some modern readers even have a hard time reading Jane Austin and wrapping their heads around the importance she places on ‘marrying well’, or, Leo Tolstoy and the absurd love many of his aristocratic character express about the Tsar in War and Peace. (And both of these writers lived during periods of transition where the subservience of women and the divine right of kings were already being questioned by various parts of the intelligensia.)

Having read two books in Thorpe’s series, it’s obvious that her world really is a fantasy instead of historical fiction. And as such she sidesteps these issues. But there is still enough of ancient Rome in the books that the idea comes to mind.

If readers are wondering what we were talking about with regard to ancient Roman statues, here’re some examples of modern recreations that archeologists believe shows what they really looked like.

I think this is enough for one article. I have enough recorded conversation for a third one, so expect that in a while.